History relates that the F1 season 40 years ago opened with the South African Grand Prix at Kyalami. What the records do not show is this race – regardless of the absence of world championship status and teams such as Ferrari and Renault – would turn out to be one of deep political significance. In fact, it would help change the course and shape of F1 forever.

The race would pave the way to previously unseen riches for the F1 teams and their leader, Bernie Ecclestone, so it was ironic that most of the participants on the day at Kyalami barely had two cents to rub together. The 1981 South African Grand Prix, despite the apparent importance of its title, was an enormous bluff.

The Formula One Constructors Association (FOCA) had been put in this position thanks to Ecclestone challenging the blustering authority of Jean-Marie Balestre, the president of FISA, the motorsport arm of the FIA. Alarmed by the rising influence of FOCA (teams such as McLaren, Lotus and Brabham), Balestre had gradually engineered a divide that saw the so-called “grandee” teams – Ferrari, Renault and Alfa Romeo – side with FISA.

Ecclestone was guided throughout by the sharp mind of Max Mosley, a lawyer and founder of the March racing team. On behalf of the FOCA teams, they put together a rival World Championship for 1981. Balestre responded by threatening punitive action against circuits staging races not authorised by the FIA, effectively cutting the feet from the breakaway series before it had a chance to get started. A pivotal moment in this increasingly divisive war happened, almost by accident, during a dinner on an Austrian mountain. “We had no money, no sponsorship, no tyres and the whole establishment was against us,” recalls Mosley. “Over the winter, Colin Chapman [Lotus], Teddy Mayer [McLaren], me and some others were skiing in Kitzbühel. At a dinner, we saw a painting on the wall of the restaurant. This piece of art had a cow in it which was being painted by a group of people. Chapman asked the waitress what it was all about. She told him about an ancient siege that had left the villagers with only one cow. To give the impression they had plenty of food, the people painted the cow differently each day and took it to a place where all their enemies could see it.

Chapman suddenly said: ‘That’s it! That’s what we need to do. Let’s organise a race.’

“Bernie liked the idea and said he could give us tyres from his old Avon warehouse. We put on a press conference in the Hotel Crillon, just next to the FIA in Paris, to announce there would be a race in Kyalami a month later, in February 1981. If Balestre had come to that breakfast at the Crillon, he would have seen what poor shape we were in. There was Mo Nunn from Ensign, who had mortgaged his house. I had to pay the airfare to Paris for Ken Tyrrell. I doubt we were even able to pay the bill in the Crillon. But we were going to hold that race, whatever it took.”

It suited FOCA that the Kyalami organisers were not particularly enamoured with Balestre. The feeling was mutual, especially following the previous year’s South African Grand Prix when, even though Renault had won, Balestre had not been allowed on the podium (a move that had been furtively engineered by the mischievous Mosley).

On the downside, of all the circuits hosting F1 races, Kyalami had traditionally been among the most financially unstable. The irony was, the rebel Grand Prix was almost guaranteed for that very reason. Kyalami Enterprises had finally succeeded in securing a lucrative two-year sponsorship deal with Nashua, starting in 1980. The continuing support of the photocopier company was contractually contingent on the running of a second Grand Prix on Saturday, 7 February. Despite Balestre’s best efforts to spike the deal, the race was on. To all intents and purposes, the 1981 F1 season started right here.

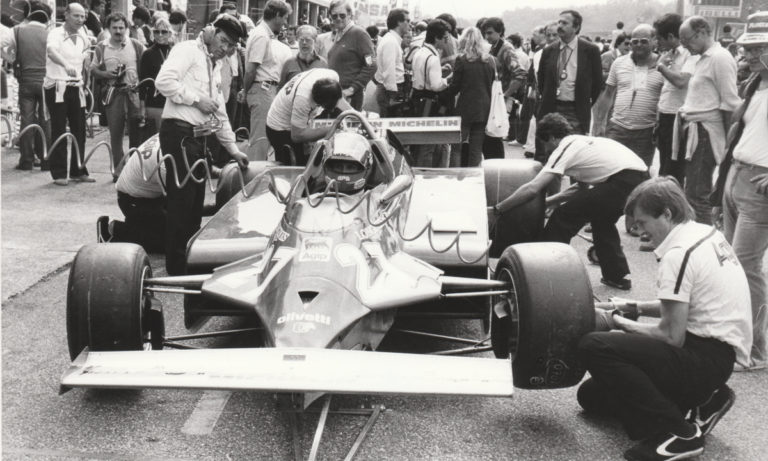

This impression was supported by a substantial turn-out of international media (including this writer); nobody seemed to mind the noticeable absence of the French and the accompanying whiff of Gauloises. BBC Radio 2 sent a reporter and BBC Television asked to show highlights during the weekend. There would be 11 F1 teams represented by 19 cars on the grid. It mattered little that 4,3 seconds separated the fastest (Nelson Piquet’s Brabham-Ford) from the slowest. This would be a Grand Prix to end the four-month drought since the previous one in the United States. Let’s go racing!

Politics counted for nothing when a wet track at the start began to dry out and throw a curveball, caught neatly by Carlos Reute- mann as the Williams driver was one of the few to gamble by starting on slicks. Never lower than eighth in the treacherous opening conditions, the Argentine moved into the lead just before halfway and stayed in command until the end of 77 laps.

The story of the Grand Prix – and that it was without Ferrari – was of no solace to an outraged Balestre, watching from Paris. FOCA had shown themselves capable of not only running a Grand Prix, but receiving international television coverage.

When Enzo Ferrari began to prevaricate in his typical desire to be on the winning side, an increasingly uncomfortable Balestre continued to see Renault as a major ally. Even though the French firm’s power and position were about to become its greatest weakness.

Having won the South African race 12 months prior and now absent, Renault panicked when Balestre threatened the organisers of the next race in California because of their support for FOCA. Renault owned American Motors and the firm’s senior management in the US were shocked when Balestre, in one of his moments of frustration, claimed Renault would not be racing in the US Grand Prix (West).

Balestre’s campaign was instantly holed beneath the waterline when Renault dared to stand up and say it would be competing at Long Beach. Although he didn’t know it, the FISA president had allowed himself to be defeated by an enemy that had run out of ammunition. One or two FOCA members could not have paid the car park charges at Heathrow, never mind the airfare had this been another rebel race.

Within weeks, a peace agreement gave each side what they had wanted: the FIA controlled the regulations and administration; FOCA would take charge of the commercial side and all that entailed. Although neither side had won in the strictest sense, the battle exposed FOCA’s financial weakness and FISA’s political vulnerability.

There can be no doubt Ecclestone was the victor and he had the 1981 South African Grand Prix to thank. The race at Kyalami may have quite literally been pointless in one sense, but it had been full of purpose in another.

“It will never be the same”– Jean Todt

Jean Todt was present at the Red Bull Ring to witness the first Grand Prix. The FIA president had a word of warning about the future.

“We are going through an unprecedented time,” said Todt. “It’s very strange here. You don’t see any traffic, any cars parked and there are empty grandstands. But when you see what has been achieved, it’s amazing and I want to congratulate all the people who have been working night and day. It has been a fantastic co-ordination between the FIA and F1 with a strong contribution from the teams. It’s been a remarkable effort and we are the only international sport that has been able to achieve that.

“The world is changing very quickly,” continued Todt. “The sport must adapt in order to move forward. We are not going to bring back the sport as it was. It will never be the same.”

The Cars

The cars taking part in the Intercontinental GT Challenge all conform to FIA International GT racing specifications. This means they are all production-based supercars with regulated modifications, such as suspension, brakes, wheels and tyres, roll cages and engine tuning. Rear wings are allowed but no major fender extensions are fitted. All cars are rear-wheel drive and include cars like the Audi R8 and Lamborghini Huracán, which in road trim would have all-wheel drive.

One of the best parts about the series is the cars are instantly identifiable with their road-car counterparts. This generates a huge amount of brand loyalty at the circuits. Engine noise is another key factor in the series’ success. Due to myriad drivetrains, each vehicle has a unique engine note and you can easily pick out the shrill scream of a flat-plane-crank V8 Ferrari 488, the exultant howl of a naturally aspirated Porsche 911 flat-six, or the raucous lowdown rumble of a Mercedes-AMG GT3. The Audi R8 LMS GT3 and Lamborghini Huracán GT3 has a raspy V10 engine note that is arguably the most identifiable of them all.

Engine outputs vary between 372 kW and 447 kW, while cars weigh between 1 200 kg and 1 300 kg. By a balance-of-performance formula, the organisers can vary the rated outputs of the competing cars. This balance-of-performance regulation is one of the reasons GT racing is so competitive, providing so many different winners. For instance, in qualifying for last year’s 9 Hour at Kyalami, the top 15 competitors were all within one second of each other during the first qualifying session.

This season, nine manufactured GT cars are eligible for the Intercontinental GT Challenge: Acura/Honda NSX GT3, Aston Martin Vantage GT3, Audi R8 LMS GT3, Bentley Continental GT3, BMW M6 GT3, Ferrari 488 GT3, Lamborghini Huracán GT3, Mercedes-AMG GT3 and Porsche 911 GT3 R.

By Maurice Hamilton